FREE range production has many positive benefits – exposure to internal parasites is not one of them. This month we discuss one of the challenges facing free

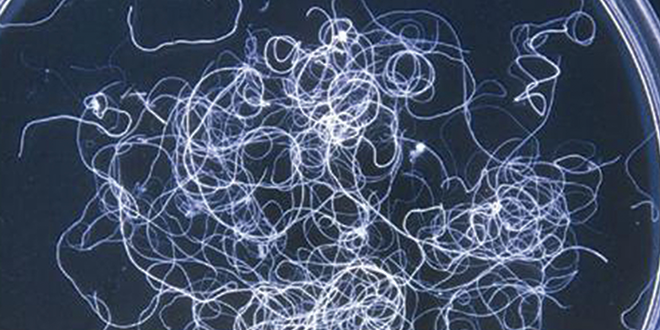

Roundworm.

range layer farming: intestinal worms.

To understand them better, we need to know more about them – their lifecycle, their hosts, their impacts and how best to control them. There are four major types of intestinal worms found in poultry: roundworms, hairworms, caecal worms and tapeworms.

Roundworms (ascaridia galli)

These are the most commonly seen intestinal worm. They are white, up to 5cm long and may be visible in droppings in heavy infestations. A severe infestation can cause a reduction in nutrient absorption, intestinal blockage and death. Occasionally, they migrate up a hen’s reproductive tract and become included in a developing egg.

This is a seriously unwanted consequence of heavy infestations. The lifecycle of roundworms is direct – eggs are expelled in the hen’s droppings and are directly infective if eaten. The eggs can survive in the environment for long periods, so are difficult to eradicate once an infection is established in a free range system.

Hairworms (capillaria)

Tapeworm.

These are much smaller (hair-like) and barely visible with the naked eye but can cause significant damage, even in only moderate infestations. There are two main species – one lives in the crop and the other in the small intestine.

Caecal worms (heterakis gallinarum)

These worms spend most of their time in the caecae. Caecal worms are generally harmless but can be the intermediary host of another parasite, histomonas meleagridis, the cause of blackhead disease. So, though chickens are generally not impacted by caecal worms, controlling the worms is still important for blackhead control.

Tapeworms

Several species of tapeworms are found in poultry. Tapeworms require an intermediate host to complete their lifecycle. These intermediate hosts include ants, beetles, houseflies, slugs, snails, earthworms and termites. They spend most of their life in the intestines and generally cause little impact on performance, unless the worm burden physically occludes the intestine.

Hairworm.

There are no approved medications for use against tapeworms, so controlling the intermediate hosts of tapeworms is vital in preventing initial infections and reducing the risk of reinfection.

The impacts of worm infestations

- Reduced vitality, poor body weight gain leading to unevenness or stunted birds, reduced egg production and egg size, decrease in shell strength and reduced yolk colour.

- Affected birds may be dull and show pale combs.

- Increased cannibalism through vent pecking due to straining.

- Death, in very heavy infestations.

Treatment options

There are only two anthelmintics (drugs for intestinal worm control) currently registered for use in Australia – piperazine and levamisole. Each of these is suitable for use in laying birds with no withholding period for eggs, while levamisole has a seven-day withholding period for meat. There are some fundamental differences between these two products – piperazine only has activity against roundworms, not hairworms, caecal worms or tapeworms.

Caeca worm.

Levamisole on the other hand is effective against round, caecal and hairworms. It is wise to rotate between the two types of anthelmintics to reduce the risk of resistance development. However there are limitations – there are no products registered for use in poultry in Australia for the control of tapeworms, so controlling the intermediate hosts of tapeworms is vital in preventing initial infections and reducing the risk of reinfection.

There are also no products registered for the control of blackhead, so it becomes even more important to control its intermediate host, the caecal worm.

Effective control of intestinal parasites is aimed at breaking the cycle of infection. Strategic use of anthelmintics during rearing will help to reduce challenge, and giving a prophylactic treatment before moving hens from rearing to production sheds will assist in breaking the infection cycle, but this needs to be combined with other good management practices such as limiting stock density on the range, rotation of the range, good drainage, and the removal of heavily contaminated soil around the shed before new pullets arrive.

Vet’s View by Rod Jenner