According to a University of Melbourne academic, the poultry industry could teach the world a great deal about the future of coronavirus infection control. Working in avian medicine in the Asia Pacific Centre for Animal Health, Professor Amir Hadjinoormohammadi said infectious bronchitis virus found in chickens had many similarities to COVID-19.

“The learnings we acquire from working with animal diseases can be applied to the way we control and diagnose diseases in humans,” Prof Hadjinoormohammadi said. While coronavirus was first detected in chickens, the term was yet to be applied to the disease.

“The disease was first reported in 1931 in America, but there was suspicion that the disease was actually present a decade earlier than that,” he said.

“The primary presentation of the virus infection is respiratory illness.

“It manifests as a runny nose, conjunctivitis or runny eyes, coughing, sneezing and quite often mortality in affected susceptible chickens.

“With a similar physical make-up, infectious bronchitis virus presented with almost identical symptoms to COVID-19.

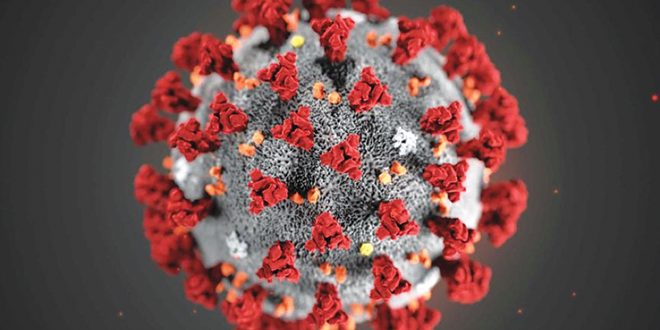

“The name coronavirus was established later, but in the 1930s they actually determined the structure and shape of the virus.” Infecting entire bird flocks in as little as 24 hours, IBV is present in most countries and spreads quickly between chickens. However, IBV could spread through viral particles and exposure to faecal matter, unlike what is currently known of COVID-19. Multiple strains of IBV are present in the world’s chicken population, and that could be vital to future COVID-19 infection control in humans.

“If you extrapolate what the poultry industry has learned with IBV, we’ll probably face the same situation with SARS-COV-2,” Prof Hadjinoormohammadi said.

“The two diseases have great similarities in terms of susceptibility to physical disinfection agents such as sanitisers that are available to us.

“Multiple attempts had been made to stamp out IBV and the poultry industry has tried hard to control the virus.

“They wanted to eradicate the disease, but soon they realised that it was impossible.

“It’s a globally important virus, found in most every country with chickens, so there has been substantial effort over the past ninety years to come up with effective vaccines.” The poultry industry had come up with different ways of vaccinating chickens.

“It’s very difficult to individually vaccinate the bird, but that is still done in several sectors of the industry,” Prof Hadjinoormohammadi said.

“Young chicks are often mass vaccinated in the hatchery due to the difficulties.

“This typically involves a spray vaccination or drinking water vaccination — quite often before the birds are transferred to a production site.

“Coronaviruses in general are very prone to changes in their genetic make-up – this occasionally causes the virus to be different in terms of its biology and the way the vaccine can provide protection.” The mutating nature of IBV often required new vaccines to protect the birds, hence, the constant evolution of vaccines was probable in the fight against COVID-19 in humans. Since the disease was reported in Australia in the 1960s, new viruses had emerged throughout the years.

“In Australia, we have at least two different kinds of vaccines that are used,” Prof Hadjinoormohammadi said.

“One of them is probably more common.

“But every so often we have a new virus emerge, and we need to come up with a new strategy to tackle that.”

07 3286 1833PO Box 162 Wynnum QLD 4178